The U.S. will withhold 15 percent of Mexico’s annual counter-narcotics grant under the human rights provisions of the Merida Initiative. American officials have signed off on the funding every year since 2007 despite ongoing objections to the country’s human right record.

What changed in the 2014-2015 fiscal year to merit the $5 million slap on the wrist? Human rights advocates told the Washington Post’s Justin Partlow that the U.S. government is finally paying attention (he broke the news on Sunday).

“It’s a big decision for them to have made,” Maureen Meyer, a Mexico expert at the Washington Office on Latin America told Partlow. “I think they basically decided we cannot honestly or in good faith say there’s been enough progress made in Mexico. It shows how concerned the U.S. is about the human rights situation in the country.”

But are human rights violations the only reason behind the State Department’s decision?

On one hand, it is hard to say if Mexican military groups are more corrupt or violent in the past year. Take the Mexican army, Sedena, whose human rights complaints peaked in 2009 and have since dropped, according to a May 7, 2015 Congressional Research Service report citing the Mexico’s Human Rights Commission (CNDH).

On the other hand, human rights violations committed by Mexican officials have been more egregious in the past year, or at least better documented.

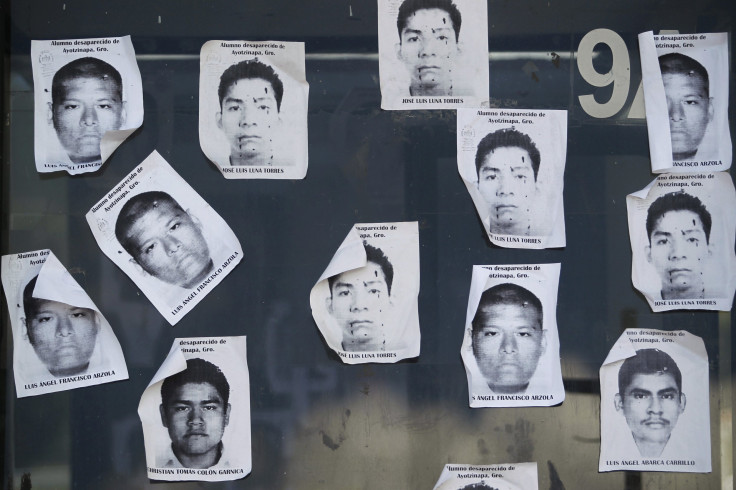

These high-profile cases include the Ayotzinapa killings last September that killed 43 student, a Sedena-led massacre of 12 people who may have been in their custody last October, and a suspected military massacre of 16 people in January, 2015.

Was El Chapo A Factor?

But there’s another piece of context: the high-profile escape of the most prized fruit of the Merida Initiative, alleged Sinaloa cartel leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. El Chapo escaped following multiple requests by the U.S. for the prisoner to be extradited. If he had been handed over, American officials argued, he would still be behind bars.

“The escape may prompt the U.S. and Mexican governments to reexamine the adequacy of Mexico's criminal justice system and anti-corruption efforts,” Congressional Research Service experts suggested following the escape, in a memo to policymakers.

Following Partlow’s scoop, the U.S. Department of State’s Deputy Spokesperson Mark Toner confirmed that it had not written a report to certify Mexico’s human rights efforts, which triggered the 15 percent ($5 million) cutbacks. But the named more than just human rights as the reason behind the decision.

“The Merida Initiative is an eight year old partnership between the United States and Mexico to fight organized crime and associated violence while furthering respect for human rights and the rule of law. [..] This year, the Department was unable to confirm and report to Congress that Mexico fully met all of the criteria [....]

"However, we continue to strongly support Mexico’s ongoing efforts to reform its law enforcement and justice systems – critical components to enhance the rule of law and protect human rights,” Toner said.

In other words, State decided that it could no longer defend Mexico’s human rights record to Congress. But how much of that decision was also linked to efforts to “fight organized crime” and failures in the arena of “law enforcement and justice systems?”

Is this a subtle message from State to the Mexican government: startup extraditions and capture El Chapo, or else? How much did El Chapo’s escape factor in to State’s decision? This question needs to be asked of the State Department and the DEA (who have a habit of not responding to our emails).

Some Merida Initiative critics say that the hundreds of deaths documented by human rights groups pale in comparison to the overall death toll of Mexico’s war on drugs. Law Enforcement Against Prohibition executive director and retired police major Neill Franklin argues that the 15 percent funding cut doesn’t go far enough.

"I want to know why the estimated 100,000* dead, and even more missing, in Mexico isn't enough evidence that the drug war itself is a human rights abuse,” Franklin told the Latin Times in an email. “We should stop all drug war funding to Mexico because it only serves to prop up cartels who terrorize the population."

Mexico, for its part, has rejected U.S. government and NGO criticisms of its human rights record but said it wouldn’t protest the funding cut.

"The way that the Department of State conducts its relationship with Congress abides the internal rules of the U.S., which Mexico respectfully observes," said Mexico’s foreign secretary, in a statement adding that “Mexico rejects any and all unilateral judgement of human rights in the country.”

© 2024 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.