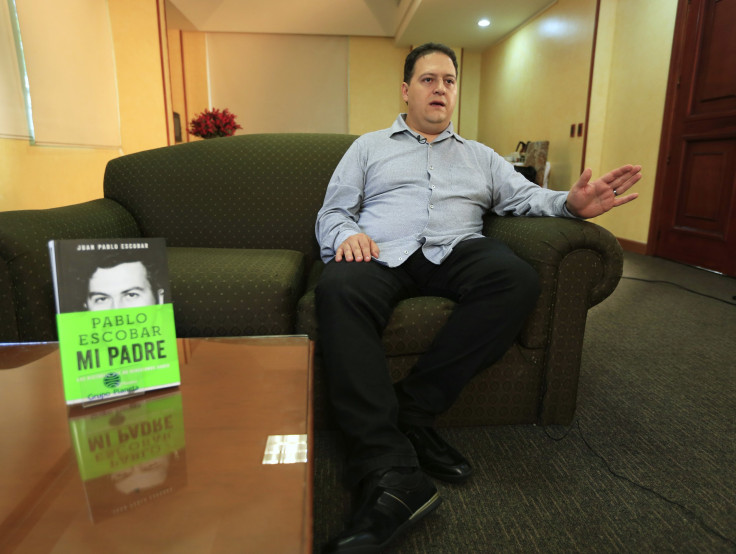

In an address to the Colombian Senate, the son of deceased Medellín cartel boss Pablo Escobar called on the government to fight drugs through education instead of enforcement. Escobar’s son, Sebastián Marroquín, made the comments at a crucial moment in Colombia’s history, as the government negotiates with the Marxist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) for a peaceful end to their 40-year civil war. Escobar, who was more of a capitalist robber-barron than a Marxist, hired FARC’s rebels to guard coca plantations in Colombia’s interior starting as early as the 1970s. The FARC eventually gained control of Escobar’s cocaine empire. Marroquín is an architect who changed his given name and has lived most of his life in exile in Argentina. He is not involved in the drug trade.

“Today after 40 years of exponentially increasing violence, we must recognize that prosecution doesn’t work,” said Marroquín, according to Radio Formula. “We must educate about drugs, not fight against them. Neither children nor adults learn at the barrel of a gun; only with love do we learn definitively and forever.”

The government has been unable to eradicate the drug trade, despite deploying many gun barrels as a part of Plan Colombia, a multi-billion-dollar U.S. aid package. The Colombian drug trade is a $10 billion business. The country produces 43 percent of global coca supply, down from 80 percent during the time of Pablo Escobar. That’s due to a shift in production to Peru and Bolivia, not a global reduction. The FARC controls 60 percent, of South-American cocaine cultivation. Colombia is now moving away from U.S. Drug War grant, and an aerial eradication program that terrorized Colombian peasants.

Though Marroquín has apologized in the past to victims of his father’s brutal reign as Medellín’s fiercest drug lord, he also reminded the Senate of his father’s Robinhood status among Colombia’s poor. In her 2013 article "Robin Hood or Villain: The Social Constructions of Pablo Escobar," scholar Jenna Bowley explains one of Escobar’s philanthropic projects, a eponymous barrio in Medellín.

“Barrio Pablo Escobar still exists today, housing 12,700 people in 2,800 homes. Its residents are Escobar’s most fervent admirers who remember him as a hero and savior. A mural is painted on the side of a building, featuring Escobar’s face and reading ‘Welcome to Barrio Pablo Escobar. Here there is peace.’”

Escobar’s philanthropy came at a time when the Colombian poor were largely neglected by the government. The situation has since improved, but peasant welfare and land reform are at the top of the agenda during Colombia’s ongoing peace talks with the FARC rebels.

“My father is venerated by the common people in Colombia because he occupied a place that the state never wanted to occupy,” said Marroquín.

Escobar’s philanthropy combated inner-city blight, and helped construct public amenities like proper soccer fields where you could play safely. In his talk, Marroquín recognized the irony of his father’s legacy. Money meant to keep kids of the streets and off of drugs was funded entirely from Escobar’s cocaine empire.

“[My father] had a crazy idea, which was to put narcotrafficking in the service of the Colombian people,” he said.

© 2024 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.