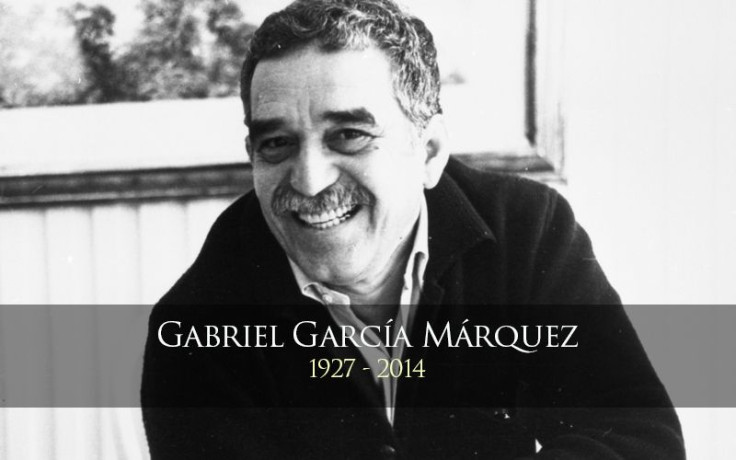

Gabriel Garcia Márquez' death has touched thousands across the world, most of all those of us in Latin America who appreciated how he understood our essence in a profound, remarkable way. Emilio Lezama is CEO of Los Hijos de la Malinche, a digital publication based in Mexico that covers news and current affairs, art, politics, literature, music, and photography. In this deeply personal essay, Lezama remembers the famed Colombian author and explains the universal appeal of Macondo.

I grew up hearing stories of the tropics. My dad and my grandparents were born in Tenosique, a small village lost amongst the Mexican jungle whose only communication with the world was through the thick waters of the Usumacinta River.

It was much later that I learned that the stories I had heard as a child were not as common as it seemed to me: that of Laura waiting by her piano a whole century for her lover to return; that of Captain Galvez who sailed the Usumacinta all the way to New York to bring back Manhattan lobsters; or the old man sitting under a mahogany tree telling children stories from the “A thousand and one nights.” In exchange for every story the kids had to pluck one of the old man’s white hairs.

I learned early on that reality and fantasy came intermingled, that life is for telling, for reinventing and not to be subjected to the rigorous and boring scruple of Western truth.

When I read One Hundred Years of Solitude it felt like my grandfather was speaking to me. Macondo and Tenosique became interchangeable and inseparable, different names that described an identical universe. When I finished the book, I closed the flap and felt a deep sense of nostalgia. As if the hundred years were now loaded on my back for me to carry. As if my veins were now curdled with the genealogy of the Buendía family.

That is why I was surprised when a French friend praised the great imagination of García Márquez. "The guy's a genius," he said " How did he imagine such craziness, so much magic." I failed to understand what he meant, there was nothing magical or crazy about Márquez it was all in fact very quotidian.

Likewise it always bothered me to learn that the West called the genre "magical realism." García Márquez was a genius, but not for the "madness and magic of his imagination" but because he succeeded, better than anyone else, in identifying the thread with which Latin America was woven.

García Márquez chronicled reality, he did not invent it. One Hundred Years of Solitude might be a work of magical realism for the West, but in Latin America it is the most important work of realism. The reality here involves the possibility of what others call magical and we call, almost with boredom, the everyday.

"One Hundred Years of Solitude , I can not read it without some dull panic. It touches deep veins of our American collective unconscious. There is in it a mythical substance, a divination load so deep, that I always lose the necessary serenity to judge." said fellow Colombian-Mexican writer Alvaro Mutis about it. More than a novel, for many, One Hundred Years of Solitude is a genealogy.

There is something devastating about the death of García Márquez which even his extraordinary literary skills do not completely justify. His irreparable loss has been the source of tears from people who never met him. In the real world, that of ordinary readers, a genuine sadness is palpable in the air. Something as certain as the existence of Macondo, as the legacy of the Buendías. Sadness, pure and simple, as sadness is.

My American friends were shocked when I showed the front pages of major newspapers in Latin America and the Spanish speaking world. It is not that García Márquez was a front page story, what shocked them was that García Márquez was all the newspaper. For practical purposes, the world had stopped, all that mattered was Gabo.

The truth is that I'm not sure if other cultures can understand the love we Latin Americans feel for García Márquez. I do not know if the XXI century and its pop culture can understand the genuine affection -and non iconic idolatry - towards a simple human being and writer. A writer who was born in the Colombian tropics and made Mexico his home, a writer that nonetheless first and foremost spoke to and from Latin America as a utopia, as a dream, as hope.

I remember the wife of another author explaining to me why One Hundred Years of Solitude meant more for them than for the rest of us. "We grew up in a town like this. It was not called Macondo but it could have been. We lived these hundred years of solitude!"

I thought of Tenosique and the green waters of the Usumacinta. I thought of it but said nothing. Each of us had our own Macondo and each of us thought we were the only ones. As if by a twist of fate, the town founded by José Arcadio was exactly like ours. Then I understood why the loss of García Márquez hurt the way it does.

García Márquez means so much because he provided us throughout Latin America with a founding myth. When creating the history and nostalgia of Macondo he gave us all an origin. All Latin America starts in Macondo.

Written by Emilio Lezama.

To see more of Emilio's work check out LosHijosDeLaMalinche.com or follow Emilio on Twitter @emiliolezama. And stay tuned for Latin Times' exclusive interview!

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.