Thursday Aug. 4 2015 marks the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which defined the responsibilities of the federal government to intervene in state elections where minority voters were being discriminated against. The legislation was one of the tangible outcomes of the mid-20th century African-American Civil Rights movement. Initially designed to combat racial discrimination, it was later expanded to protect other minorities, like Latinos who were denied equal access to voting if they were Spanish speakers. What did the VRA change? Let us quickly travel back to the end of the Civil War.

Abraham Lincoln may have freed the slaves, but he didn’t ensure African-American citizens the right to vote. By 1870, America ratified the 15th Amendment which guaranteed the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Pretty clear, right? But while the federal government is bound to protect the constitution, it doesn’t directly run elections. That duty is left to the states, where some were not happy that black men could vote. In the 100 years that followed states sidestepped the 15th amendment, intentionally discriminating against minority voters. For example, some southeastern states culled black voters from the rolls with literacy tests and poll taxes, while excluding less literate or poor whites with “grandfather” clauses.

The VRA allowed the federal government to oversee voting rules in troubled southern states and ended the worst examples of taxes and testing. Over the years that power expanded to Alaska, Arizona and Texas, as well as parts of California, Florida, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, and South Dakota. Some jurisdictions have come off the list if they’ve “proved” they can make their own rules without discriminating against minorities. Texas has recently argued that it should no longer be subject to VRA oversight.

1) English Literacy Tests Were Imposed On Spanish-Educated Puerto Ricans

Discrimination against minority voters wasn’t just a Dixie thing. In New York, literacy tests in English helped Yankee racists exclude Spanish-speaking citizens like newly-arrived Puerto Rican migrants. Educated in Spanish-language schools in Puerto Rico, some Nuyoricans couldn’t pass the tests. It wasn’t because they were illiterate or uninformed; they just got their news and electoral coverage in another language. In Katzenbach v. Morgan, the Supreme Court upheld the federal government's right to protect Spanish-speakers against unfair tests.

“[In] the context of the large and politically significant Spanish-speaking community in New York, [it] serves no legitimate state interest [...] and is thus an arbitrary classification that violates the Equal Protection Clause,” the majority wrote in 1966.

The VRA would later be expanded upon to ban all literacy tests and to include “linguistic minorities” under its protections.

2) VRA Extended To Latinos Further In 1975

For most Latinos 2015 is actually the 40th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act. Even though Nuyoricans used the VRA as a tool in the case of literacy tests, there were still other forms of discrimination that prevented Hispanic communities from fully participating in the democratic process. In 1975, President Gerald Ford signed into law an extension of the Act, including linguistic minorities such as Mexican-Americans, indigenous groups and others. Suzanne Gamboa of NBC explains the significance of the extension in a recent piece, drawing on an interview with Luis Fraga, a politics professor at Notre Dame's Institute of Latino Studies.

“Extending voting rights protections to Latinos made it possible to translate registration materials into Spanish, launching larger Latino voter registration drives. It also gave power to Latinos to begin to build political influence, to bring court challenges against discriminatory redistricting and election systems that kept Latinos from electing Latinos to public office,” Gamboa wrote.

3) Latinos’ Continue To Be Excluded In Local Politics, Activists Say

In some states, Latino groups have focused on at-large election systems. They are common in school boards and other important local bodies that decide how taxpayer money will be spent. Critics say that this type of districting discriminates against minorities.

“At-large systems allow 50 percent of voters to control 100 percent of seats, and in consequence typically result in racially and politically homogenous elected bodies,” according to FairVote, a progressive voting rights think tank. “At-large systems have frequently been struck down under the Voting Rights Act for not providing communities of color with fair representation.”

Those accusations are not ancient history.

4) Statewide Voting Right Acts Built On The VRA

Latino legal advocacy group Maldef continues to file discrimination complaints against at-large election systems using California VRA laws. California passed its own Voting Rights Act in 2002, allowing the state to intervene in at-large elections in minority communities, a sort of boostershot to the federal VRA. Maldef has used the California law to challenge governance structures everywhere from school boards to public utility boards as recently as last week .

5) The VRA Was Gutted in 2013, Latino Advocates Want It Back

In 2013, the Supreme Court invalidated sections of the VRA, allowing Texas to change voting requirements without the approval of the federal government. Concerned about voter fraud, including alleged voting by non-citizen immigrants, the state wanted to strengthen voter ID requirements. Ahead of the judgement, Columbia University political science professor Rodolfo O. de la Garza authored an op-ed in the New York Times entitled The Voting Rights Act Protects Latino Voters . He disagreed with Texas’ argument that the VRA was outdated, saying the assertion “ignores Latino experiences.”

“In Florida, The Miami Herald found that the Republican-controlled election supervisors targeted Hispanics much more than Anglos for removal from the eligible voter list. In Arizona, the Spanish language electoral materials the state is required to publish and distribute erroneously announced the election would be held on Nov. 8, but the English language section of the documents listed the correct date of Nov. 6,” he wrote.

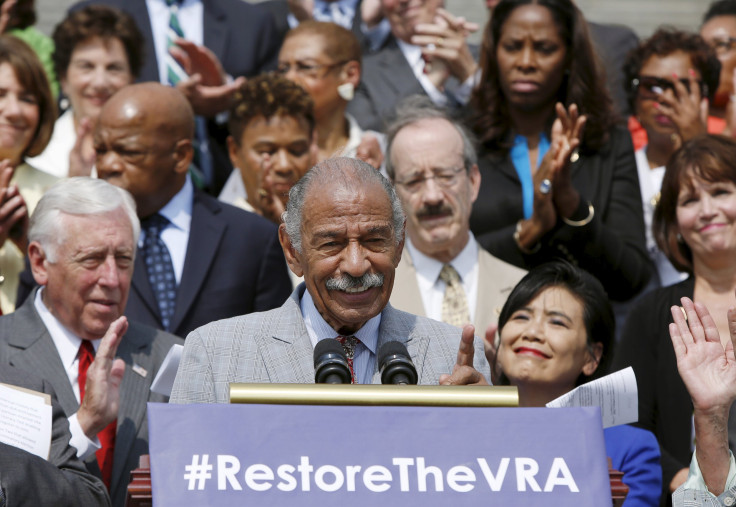

Maldef has supported legislation to undo the losses of the 2013 decision, and Democrats have rallied around efforts to “restore” the VRA. Democratic presidential candidate Martin O’Malley has proposed a constitutional amendment that would take the VRA even further. Restoring the VRA would protect 4.5 million eligible Latino voters, according to Naleo.

6) A Weakened VRA allowed Voter ID Laws In Texas, Called A Modern “Poll Tax”

At the forefront of the current VRA nostalgia is Texas’ voter ID laws, which enact strict requirements for voters to cast a ballot. There has always been a cost to voting in terms of time or transportation if not actual dollars (e.g. postage for absentee ballots). However, Texas wants its voters to present a photo ID before they vote, a requirement that can’t be met without paying an actual cash fee. While it might sound surprising, around 10 percent of the voting population doesn’t have a form of ID like a driver’s license or a passport. That includes 25 percent of African Americans and 8 percent of whites, according to Politifact (there aren't any reliable stats on Latinos).

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg called voter ID a “poll tax” in her dissent to the 2013 gutting of the VRA.

“The greatest threat to public confidence in elections in this case is the prospect of enforcing a purposefully discriminatory law,” Ginsberg said in a dissent against the 2013 ruling quoted by Salon.com, “one that likely imposes an unconstitutional poll tax and risks denying the right to vote to hundreds of thousands of eligible voters.”

On August 2, 2015, the Texas voter ID law was ruled as unintentionally discriminatory against minority voters by the conservative 5th Circuit Court. In response, Gov. Greg Abbott said in a statement that his attorney general would appeal the decision.

“In light of ongoing voter fraud, it is imperative that Texas has a voter ID law that prevents cheating at the ballot box. Texas will continue to fight for its voter ID requirement to ensure the integrity of elections in the Lone Star State.”

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.