“President Obama Goes To Prison,” the headlines read. In an unprecedented gesture for prison and sentencing reform , Obama is scheduled to visit El Reno, a medium-security prison in Oklahoma on Thursday. It is the first time that a sitting president walks the halls of a federal prison.

Though the White House hasn’t confirmed the details, Barack Obama is highly likely to visit with inmates at El Reno. At least one current inmate is being vetted to meet the president, according to information provided to the Latin Times by a prison reform activist on the condition of anonymity. The planned visit follows a push to deal with the ballooning U.S. prison population of 2.2 million . That number, Obama argues, is a consequence of overzealous drug enforcement: Since 2010, the Obama administration has stated that its goal is “ evidence-based public health and safety ” and a reduction in incarceration.

Arguably more important than who goes into El Reno on Thursday is who will come out in the near future. On Monday, Obama issued the latest in a series of executive orders that commuted sentences of nonviolent drug offenders serving long prison sentences. A commuted sentenced is a reduction, not a forgiveness, but it's often used interchangibly with "clemency."The first wave, announced in December 2013, shortened the sentences of eight felons. The second wave, announced on Monday, will result in the early release of 46 prisoners. The vast majority of those offenders served at least 15 years and were sentenced to between 25 and life without parole — under sentencing guidelines that have since been changed.

More prisoners at El Reno are hoping to get their sentences commuted. Even if they succeed in their petitions, they face a high chance of ending up back in jail. Over 75 percent of prisoners are arrested within five years of their release and more than half within one year, according to a 2005 study by the National Institute of Justice.

How many of Obama’s commuted prisoners will be back in jail? For President Obama, releasing these prisoners is a political risk. For felons, avoiding crime is a personal struggle. For companies looking to employ a low-skilled laborer, hiring a felon doesn’t make a lot of sense. Prisoners were reminded of these realities in a form letter from the President.

"I wanted to personally inform you that I will be granting your application for commutation [....] It will not be easy, and you will confront many who doubt people with criminal records can change,” reads part the letter . “Perhaps even you are unsure of how you will adjust to your new circumstance."

Jason Hernandez

Who are these felons who will attempt to rebuild their lives outside the walls of prison, and how has mercy from the Oval Office affected their journey? To find out, I spoke with Jason Hernandez, of McKinney Texas, one of the eight felons who received commutations in 2013 and has since left El Reno. Hernandez, 38, is still technically in custody; he’s not “released” until August 11 of 2015, but he was out of prison in 2014. He’s now at his parents house under house arrest, which means that he can leave house for work and other approved events.

Hernandez first reached out to me on Facebook. I’m used to getting lots of P.R. pitches on behalf of authors, politicians and even CPAs. This message was very different.

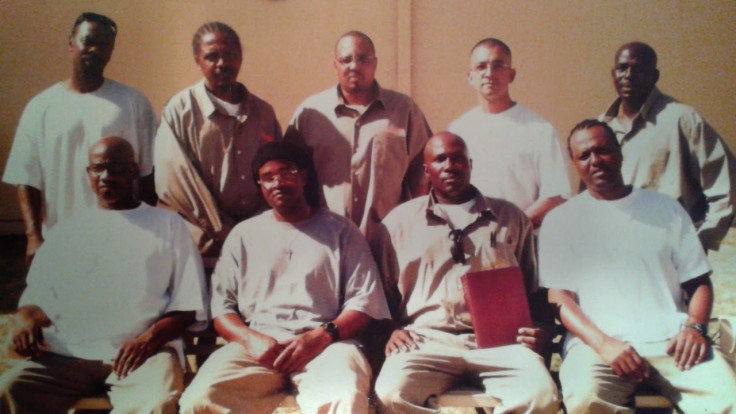

“I think you would find my story very educational to our people about the War on Drugs and how it has resulted in prisons being filled with Hispanics and our communities destroyed,” he wrote, including links to his interview from prison with Democracy Now , his sentencing website (operated by a relative). This week, he sent me photographs from in and outside prison. Next to bulky African American inmates, he looks skinny, almost meak. In work uniforms, Hernandez appears clean cut, a thin beard and short-cropped hair. This week, he called me from his parents house in McKinney, an hour outside of Dallas. He addresses me as “sir” and “brother” intermittently, simultaneously displaying the discipline of a behaved inmate and the warmth of a free man.

Crime And Punishment

Hernandez was a drug dealer from age 15 to 21, following the footsteps of his brother in a neighborhood where “everyone was dealing drugs or using drugs.” He was arrested and sentenced in 1998 for possession and sale of crack, along his brother and their supplier who was caught with a similar amount of cocaine. Because of mandatory sentence enhancements for crack, Hernandez got life. His supplier got 12 years.

“Everything he did, I did. Started with an ounce of marijuana and moved to kilos of cocaine,” Hernandez told me over the phone. “I was obsessed with becoming a big time drug dealer. And I was so obsessed that I got a life sentence. I was so good at it thought that I was born to deal drugs. When I went to prison -- every day and night I just thought about how I could get out of prison. ”

It wasn’t just prison bars that rattled Hernandez’s love of the criminal lifestyle, but matters of life and death. His brother, who had a release date, was stabbed to death in a prison fight in 2002. Meanwhile, Hernandez’s son was growing up without a father.

“My son was 7 months old when I got arrested. It’s hard to build a bond with a child in four hour visits every three or four months,” Hernandez said, pointing out that the drive from McKinney to Oklahoma is six hours. “He got older, and stopped coming to visit.”

Ex-Con

It’s notoriously difficult for ex-felons to get work, though some states are trying to change this. Hernandez and convicts like him carry the stigma of a felony as well as a decade or more long gap in their employment history.

Not only do they carry the stigma of a convict, but after years or more in jail, they have no job experience to speak of. Hernandez, though, had a trade skill.

“I took a welding class taught to me by another inmate who was serving life without parole,” Hernandez said.

That welding teacher was Altonio O'Shea Douglas, another non-violent drug offender. (Both Douglas and Hernandez were named in in a 2013 ACLU report entitled “A Living Death: Live Without Parole For Nonviolent Offenses,” both were held up as the epitome of a justice system gone haywire; young men taken out of society permanently when then might have been reformed. Hernandez credits Douglas for teaching dozens if not hundreds of inmates the craft of welding.

Still, Hernandez faced challenges finding jobs. For one thing, he didn’t know how to use a computer. Sentenced in 1998, the same year that Google hired its first employee and the rest of us were plugging AOL disks into our Windows 1995 machines, he’d barely even seen one. It was embarrassing, he remembered.

“I would go apply for a job and they would say go over there; they’d point to a computer,” Hernandez said. “I’d would say ‘I’ll come back later.’”

Hernandez kept going to job interviews. His felony conviction wasn’t a deal breaker for entry-level welding jobs, but his long sentence made employers suspicious.

“Everybody was like ‘well, everybody goes to to prison.’ I would say 17 years. Their eyes would open, and they would say ‘look: some there's something you must not be telling me; you must have been connected to a cartel or done kidnapping or something.’”

After having this happen a few times Hernandez bought his clemency with him to his next interview, a full-time spot on a welding crew that would net him $14.50 an hour. It was a longshot application already: the Dallas staffing agency was looking for someone with work experience, which Hernandez didn’t have. They wanted him to work certain hours, which his virtual house arrest couldn’t accomodate.

“I pull out my folder and I say ‘the President of the United States granted me clemency,’” Hernandez said. “They held it up, and showed everyone in the office. They told me, ‘We’ll give you a chance. We love your story.’”

Caring Cook

Hernandez was already turning his life in the early 2000s when he ran into his former drug supplier in jail. The man had escaped from a minimum security camp and evaded authorities for four years before being recaptured. In prison, he was still dealing drugs, according to Hernandez, bringing in marijuana from the outside.

When I asked Hernandez if he ever ran a hustle in prison, he immediately said “yes.” It was misunderstanding. I meant smuggling contraband, but Hernandez thought I was referring to something -- legal or illegal -- that made money in prison.

Imagine my surprise when he explained that his “hustle” was cooking empanadas.

Hernandez explained that in El Reno, prisoners can buy food at the commissary, cook it and sell it to fellow inmates. At the height of his “operation,” Hernandez said that he sold 300 empanada per week.

“We sold them $1.50 for one, and a discount for five. They paid us in stamps,” he said.

“They didn’t pay you in cigarettes?” I said, thinking of the prison scenes from Rounders.

Hernandez politely explained that inside El Reno, stamps are the defacto currency. Cigarettes were tightly regulated started in 2005. Also, there’s a conversion rate. Buy a 41 cent stamp from the commissary, and it’s worth 30 cents to other inmates. To move that money into the outside, there’s another fee. Hernandez said he would pay another inmate $120 worth of stamps (at the 30 cent rate) to send $100 to his son for Christmas.

He explained this to me without any bitterness. At every stage of the conversation, he’s upbeat. At one point he tells me that, his own supportive father notwithstanding, he sees Obama as paternal figure. Half-jokingly, he tells me that he’d like to be back in El Reno for a chance to the President.

“I was dead, I was supposed to die in prison ... he gave me my life back.”

Unlike a felon who serves their sentence, convicts like Hernandez get a sort of moral boost from commution. Hey haven’t just paid back their debt to society, they’ve been given a second chance

"I believe in your ability to prove the doubters wrong, and change your life for the better," reads Obama’s form letter to each recipient of a commuted sentence.

On the outside, Hernandez now works two part-time jobs, one as a welder at a car shop where installs specialty mufflers and spoilers and another as a cook at Cafe Momentum , a restaurant that that employes post-juvenile offenders who’ve done time in the Dallas area. It’s a haven for second chances, where young kids with criminal records put out $20 plates and fourth courses. Hernandez started at Momentum as a volunteer. Now his title is Kitchen Mentor, and he supervises the “interns” -- entry-level cooks, waiters and dishwashers who are all paid the same starting wage of $10/hr.

“I felt like I wasn’t touching lives with welding,” Hernandez said, who added that he’s grateful to his new welding boss, who took a chance on him and who offers him a wage that makes it it viable for him to work at Cafe Momentum part time.

Who’s Next?

Hernandez’s welding teacher Altonio O'Shea Douglas is one of the inmates likely being vetted to meet with President Obama in person during the visit to El Reno prison, according to Latin Times’ source. His case has had the attention of the ACLU and NAACP . He’s the kind of inmate that gave Hernandez a version of survivor’s guilt -- why was his petition accepted when Douglas’ was not? In any case, Hernandez said he’s ready to help his friend adjust to the outside.

“If [Altonio] were to get out, I could get him a job easy, maybe making about 1,000 a week,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez isn’t just worried about Altonio. He’s worried about other inmates, and with his Latino heritage he thinks that’s where he can help. Latino drug offenders are 40 percent more likely to get sentenced to prison than white offenders; African Americans are 20 percent more likely, according to the Sentencing Project . Of the 2.2 million prisoners in the U.S., 1.5 million are nonviolent drug offenders, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. In federal prison, drug offenders (violent and nonviolent) make up 50 percent of the prison population. The next largest group? Immigration violators, at 10 percent.

Hernandez is writing a manifesto entitled “Brown and Out” with the subtitle “The War on Drugs has crippled Hispanics and their communities just as much as this country’s immigration policies, so why are Hispanics doing nothing about it?” In it, he argues that felons and undocumented immigrants are in a similar boat: They are second-class as a result of breaking the law. He calls on Latino organizations like the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) to get more involved with prison issues. It’s ironic, he argues, that his successful clemency petition was supported by the very white ACLU.

**Update: you can read Hernandez's manifesto on Latino Rebels**

Hernandez has escaped “a living death,” but he and his family bear the scars of his mistakes. His son is distant. They’ve seen each other since Hernandez got out, but the relationship is still cold.

“I call him, I talk to him. He doesn’t call me dad. He doesn’t say ‘I love you,’” Hernandez said.

Some of his relatives have blamed the boy for disrespecting his father, but Hernandez blames himself — though entwined with his regrets, I sense a glimmer of hope and an indomitable confidence in his voice.

“I wasn’t there for him. He’s 18 years old now. It’s gonna take time.”

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.