As the Trump administration intensifies its immigration crackdown and legal protections for migrants shrink, Central American immigrants are sending more money to their home countries driven by uncertainty, fear of deportation, and the looming implementation of a new tax on remittances.

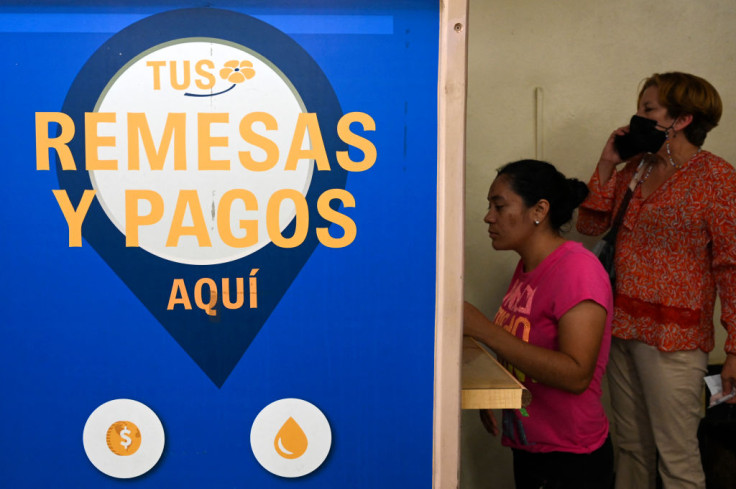

Remittance storefronts across the U.S., particularly in areas with large Central American populations, have seen a surge in activity as immigrants from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala wire more money back home, anticipating they may soon lose access to their savings if deported or forced to leave, he Washington Post noted in a new report.

"People who've saved up money don't want to keep it here," said Javier Guzman, a Honduran immigrant in Maryland to the outlet. "There's a fear that they might not be able to access it otherwise."

The trend seems to span immigration statuses, as longtime residents with Temporary Protected Status (TPS), newer arrivals working in food service or construction, and even green card holders say they're feeling increasingly vulnerable.

"The common perspective is that [Trump] is going all the way on immigration," said Manuel Orozco, director of migration programs at the Inter-American Dialogue. "If you're detained, you won't be able to keep sending money."

Remittances to El Salvador rose 14% from January to March compared to the same period last year. In Honduras they saw a 20% increase and in Guatemala they rose by 21%. These transfers now make up over 20% of GDP in many Central American nations, and amount to more than $45 billion annually for the region.

On the flip side, remittances to Mexico—a much larger recipient of migrant cash—have seen their steepest drop in over a decade. Mexico's central bank reported a 12.1% drop in remittances this April, which analysts attributed to fear-driven changes in migrant behavior and a weakening U.S. job market.

The Trump administration's proposed remittance tax, set at 1% under the recently signed One Big Beautiful Bill Act, has further motivated some to send larger sums ahead of its implementation. Though digital transfers are expected to be exempt, those relying on cash services may be affected.

"It's just in case something happens to you as an immigrant," said Raúl Castro, a Salvadoran Uber driver in Virginia who now sends more money to relatives despite limited financial obligations in El Salvador. "It's easier to have an escape plan."

For many, remittances are becoming both a financial strategy and a form of security too. As restaurant worker Yheimmy Poma put it:

"It's affecting us more because we're the ones sending money to our families. God willing, I will be able to go back."

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.