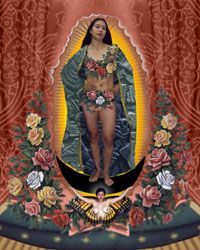

“I chose to portray her in an uncolonized state of being,” says Albuquerque resident Ungelbah Davila. The woman under Davila’s skin has black hair, her skin the color of Davila’s skin. The tattoo differs from traditional representations of the Virgin of Guadalupe found in churches like Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, where authorities anticipate seven million pilgrims with gather today for the patroness’ annual feast celebration, also a Mexican holiday. Davila’s Guadalupe wears a dark, star-studded cloak which covers her arms and hips and one of her breasts. The rest of her body is uncovered, framed by red roses and yellow maize.

The Virgin of Guadalupe is one of many revered apparitions of the Virgin Mary, known in the Bible as the mother of Jesus Christ. There are many other apparitions of virgins, such as Our Lady of Fátima, whom Pope John Paul II credited for saving him from a bullet wound he suffered in 1981.

The Vatican embraces apparitions of the Virgin Mary, but does not require Catholics to believe in them or their capability for intercession. Unlike confession or baptism, devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe is optional. Davilla and other modern devotees (usually on the less Catholic end of the spectrum) often decouple her connection to the church and trace her origins to Aztec gods.

“I would describe myself as more of a Pagan,” Davila says, adding that she relates to Guadalupe simultaneously as a woman of color, as a Hispanic and as a Navajo.

The madonna drawing so many pilgrims on Saturday gets her name from guad , the Arabic word for river or valley and lupus , the Latin name for wolf. Mexico’s Guadalupe is not the first. Another dark-skinned virgin drew worship centuries before her in medieval Spain, where she is a moorish-looking maid whose altar is still maintained in the Southwestern province of Extremadura.

In 16th century, Extremadura was home to many of the soldiers that fought for the Spanish Crown including Hernán Cortés, the stubborn commander who led the conquest of the Aztec empire. In New Spain, Guadalupe eventually became an icon among Aztec Catholic converts.

The Vatican credits a Náhuatl man called Juan Diego for seeing the Virgin of Guadalupe appear to him in 1531, just a decade after Cortés’ initial sacking of Tenochtitlán. According Church dogma, the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared to Diego and commanded him to build a Cathedral in her honor.

Miracles ensued, including a winter flowering of Castilian roses and what the church considers a divinely created image of the patroness, now on display in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The origin of the image is still disputed among theologians and secular academics.

The ubiquity of modern representations in Mexico and Chicano culture is undeniable. I was reminded of this by my former academic advisor at Middlebury College, Professor of Spanish Dr. Patricia Saldarriaga.

“People are using Guadalupe in contemporary Mexico as a sign of identity,” she tells me over the phone, adding that images of the Guadalupe “are on shopping bags, dresses and even guns.”

Controversial Representations

I met Davila in Santa Fe, where we both group up and where a controversy over modern representations of the Virgin of Guadalupe raged when we were in high school. It was the beginning of the digital image revolution. Photoshop was not a verb yet. In Feb. of 2001 the Museum of International Folk Art presented a collection of pieces by Hispanic female artists that included multimedia circuitry and digital collagest.

Titled Cyber Arte: Tradition Meets Technology, the exhibit drew ire from elements of the Spanish Catholic community over "Our Lady," a digital collage portrayal of Guadalupe by L.A. Chicana Alma López using photographs of a live model whose private parts were covered with flowers. Compared to other art controversies, the New York Times wrote, it seemed “rather innocuous.”

Yet some local Catholics demanded that the piece be removed. Some sued the museum, and pursued a political campaign in the state legislature to defund it. This was the dawn of the internet, but hate and fan mail flowed to Lopéz, who archived hundreds of the on her website . That was the easy part.

“The protests were violent,” López says in an interview with the Santa Fe Reporter in 2013. “The museum, the curator and I endured constant verbal abuse and physical threats.”

Then-curator Dr. Tey Marianna Nunn remembers being followed on the street. At she contented to have the FBI tap her phone to record various death threats. Even after the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York, attention was strong enough to wage a local campaign of threats, lawsuits and intimidation.

It wasn’t so much a battle between religious and irreligious ideas, Nunn explains to me in a phone conversation. Lopéz was baptized and raised Catholic. She held a sincere affection for La Virgen . But she was also a California Chicana, seen as an outsider by some Northern New Mexico Hispanics.

Nunn, who is now the Museum and Visual Arts Program Director of National Hispanic Cultural Center, is still shaken up when remembering the aftermath of the exhibition.

“Most of the voices of protest were men,” she says, noting that the show . “I remember attending a meeting [to address community concerns] and we were surrounded by a [mob of men] that yelled ‘burn her, burn them,’ before being whisked away by two U.S. Marshals.”

“Burn him” is the mantra of Santa Fe’s Zozobra effigy burning ceremony, the highlight of a week-long fiestas celebration focused on Hispanic heritage and the colonial history of the town. Ahead of the ceremony, townsfolk write their discontents on scraps of paper, which are burned with the 40ft. effigy, dubbed “Old Man Gloom.”

I first met Nunn as a teen, performing in a the fiestas parade that precedes Zozobra. It included men riding on horseback dressed in armor and decorated with spears and conquistador-style helmets, some carrying banners with their family names: Ortiz, Ramos, Oñate. In other words, we participated and felt like we are a part of that Hispanic community.

At the time, I didn not know how much she had gathered so many zozobras -- inquietudes during the fallout.

“Religion is emotion,” Nunn tells me. “I had friends telling me ‘I can’t be your friend anymore.’”

Often forgotten in the aftermath of the controversy was Our Lady’s model Raquel Salinas, who reported that participating in the project had helped her recover from a sexual assault saying “I feel good about my body [now]. I carry no shame anymore.”

The archbishop of Santa Fe, Rev. Michael J. Sheehan shamed Salinas, López and Nunn, saying that they had turned his Holy Virgin into a “tart,” a slut.

A History Of Appropriation

Saldarriaga, is on a one-year sabbatical to investigate the relationship between the Virgin of Guadalupe as a religious icon and its appropriation as a symbol of nationalism. While she is mostly looking at the transformation through Baroque-era poetry, there are elements of this appropriate that we can see.

Consider, for instance, that the angel below Guadalupe has been portrayed with Mexico’s national colors since the early clamors for independence from Spain, a choice that actually subverts the interests of the church in its centuries-long war with secular governments.

In modern times, secular Anglo culture has appropriated the Guadalupe as well. In the gentrifying side of San Francisco’s historic Mission district, I spotted more tattoos, along with high-riding Lupe socks (which I bought, and have worn to salsa dancing, mass and job interviews). In Santa Fe, it is not uncommon to see this bumper sticker: In Guad We Trust.

"Juan Diego is a narration, [whose] history has never been proven," says Father Olimon, a founding professor of the Pontifical University of Mexico, and priest at the Diocese of Tepic in western Mexico, in an interview this week with the The Catholic Currier . In his 2001 book, The Search for Juan Diego Olimon questions the the existence of St. Juan Diego's existence.

Over the phone, Saldarriaga tells me that the supposedly divine image was infact a painting executed by an indigenous artists. The Juan Diego story was written about 100 years after the fact, in Miguel Sánchez’s Imagen de la Virgen Maria, Madre de Dios de Guadalupe .

“Basically, he constructed this miracle,” Saldarriaga says. “[Only] after the book is published do [we] start seeing an emphasis on apparition and God’s authorship [instead of the indigenous painter].”

This narrative is on display in museums from Mexico City, to Madrid, to Los Angeles, where the 17th and 18th century paintings inspired by Sánchez often show Guadalupe at the center, with insets around the edge telling his new narrative.

Despite disagreement inside and outside of the church as to to the veracity of the cloth and doubts that Diego was a real person, he was beautified by John Paul 11 in 1990 and canonized in 2002. Diego was Latin America’s first indigenous saint.

But an endorsement from the church hasn’t swayed the hearts of Mexican Catholics. Devotion to Santo Diego takes a backseat to adoration of the patroness of the Americas, and his Dec. 9 Saint’s day attracts few from the flock. Nor has debunking of the Guadalupe myths detracted from her popularity.

“Many people in Mexico know it is not true,” she says, agreeing that the origin of Guadalupe doesn’t tether the modern meaning of the Mexican Madonna, who has long-since escaped the walls of Mexico’s churches. Guadalupe's folk appeal carries on.

Modern Affection For La Virgen

Davila says that her tattoo raises eyebrows, and sometimes older men will use it as an invitation to start hitting on her. Your boob is showing , they’ll say. Yet despite living in Santa Fe and Albuquerque, she has never had anyone confront her about it.

“I remember one little boy was 5 and he said ‘she’s not wearing any clothes.’ His litter sister, who was 9 corrects him and says ‘she’s just beautiful and she’s showing everyone how beautiful she is. That girl is the only one who has ever really gotten it. I’m not sexualizing [the Guadalupe], otherwise I’d get a Bettie Page tattoo.”

The owner of La Loca Magazine, Davila produces rockabilly style pinups that are a bit closer to Bettie Page. Also the Director of Communications at EFG Creative, Davila often puts that kind of sexiness into advertising and social media pushes. But that’s not the approach she takes with the Guadalupe.

A recent issue of La Loca focused on Chicano/a identity included a representation of The Virgin in a photo-shoot, but it was far less provocative that the regular centerfolds. It also showed the influence of López, the artist who produced “Our Lady” and the path left blazed by hers and other early experiments.

According to Dr. Nunn, the curator, reinterpretations of Guadalupe were common by the 1970s, especially in Chicano/a cultural hubs like Los Angeles. She had become one of the few Latina gallery curators in the country with a PhD, she always wanted to show the strengths and modern relevance of Hispanic art, something she didn’t see much of in the national galleries in Washington, D.C.

Focused on the pushing Latina art forward in a world where those narratives were often crowded out, The 2001 controversy kind of blindsided her, kind of traumatized her. But she stands by her decision and remains confident that she didn’t intentionally offend traditional notions of marianism.

“People ask me if I would do it again,” she tells me, “and I always say ‘yes,’ I would do it for that show. The intent was to show computer art. If [the show] had been about traditional portrayals of the Virgin I wouldn’t have done it.”

Deadly Appropriations

It is worth noting that unlike the flocks offended by, say, the Charlie Hebdo cartoons or Salman Rushdie’s portrayal of an Islamic prophet as a homosexual, none of the violent threats from the Guadalupe art dissenters caused physical harm. The stalking, the harassment, the death threats -- they terrorized López and Nunn but can’t be brought to the level of the Paris attacks.

Yet the droning call for censorship over the Guadalupe continues. In 2011, the Oakland Museum was targeted for an exhibition that included a portray of the madonna. In 2013, the cover of the Santa Fe Reporter angered locals. In 2014, it was a morbid painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe by Paz, a white male artist, who had combined her with other goddesses, including a necklace of skulls for a Santa Fe gallery.

"I don't think this should offend you because this is my interpretation of it. Your religion is your religion and an image shouldn't be bothering you in that way and if it is your faith isn't that strong,” Paz told a local TV station in 2014.

His painting relatively more scandalous than Lopéz’s. But despite being non-Hispanic and non-Catholic, Paz didn’t incur the same level of wrath from the local community. Maybe it’s because his piece was in a private gallery, or maybe the town’s knee-jerk reaction is just getting more geriatric and numb internet age.

In Mexico, there’s a more concerning trend. If portrayals of Guadalupe as partially or fully nude seem sacrilegious, consider reports that narco soldiers are putting her image on her guns, maybe even calling on her to expedite the deaths of their enemies.

That’s become a zozobra , a concern, for Saldarriaga perhaps connected with the way that Mexican society itself esta zozobrando (keeling over) in the midst of contemporary cartel violence. Over 164,000 people have been murdered in Mexico since 2007 according to Frontline, more than the combined death toll of the Iraq and Afghan wars in the same period.

When Guadalupe isn’t being called on by sicarios, she’s competing with Santa Muerte, a death cult popular among cartel soldiers living fast and dying young. The government has seen this religiosity engraved on pistol grips in the shape of Saint Jude (the patron of lost causes) and Guadalupe herself.

“The moment you have [Guadalupe’s] image on a gun, you’re justifying injustice,” Saldarriaga says.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.