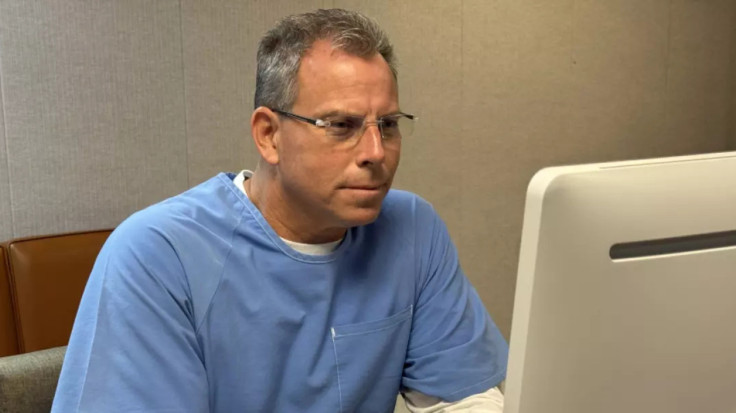

Erik Menendez, one of the Menendez brothers convicted of murdering their parents in 1989, faced the California Board of Parole this week. The hearing marked a grim milestone: 36 years and one day since his family first learned José and Kitty Menendez were dead.

"This is the day all of my victims learned my parents were dead," Erik told the panel, according to a media pool, including Los Angeles Times and TMZ following the meeting. "Today is the anniversary of their trauma journey."

But after hours of questioning, the board denied his release, ruling that Erik still poses an unreasonable risk to public safety. He will not be eligible to petition again for three years.

Contradictions in His Testimony

The Menendez brothers have long argued that the killings were motivated by years of sexual and emotional abuse at the hands of their father. Supporters describe the crime as an act of self-defense.

During Thursday's parole hearing, however, Erik complicated that narrative. At one moment he said the shooting was not self-defense, then moments later he insisted he feared his father was about to rape him.

On the night of August 20, 1989, Erik said he was convinced his father would sexually assault him and that his life was in danger. When asked why his mother was also killed, he explained that the revelation she had known about the abuse was the most devastating moment of his life. "On that night I saw them as one person," he said.

A Record of Prison Violations

Much of the board's questioning focused on Erik's behavior in prison, where he has spent more than three decades. While family, advocates, and fellow inmates have painted the Menendez brothers as model prisoners, records tell a different story.

Board of Parole Commissioner Robert Barton cited "a laundry list" of violations. These included fights with inmates, contraband cell phones, alcohol use, and ties to a prison gang involved in tax fraud.

One of the most serious incidents occurred in 2013, when Erik admitted to helping a gang known as the "25ers" run a tax fraud scheme. He said he saw it as a way to protect himself in a violent prison environment. "When the 25ers came and asked for help, I thought this was a great opportunity to align myself with them and to survive," Erik told the board.

Cell Phones, Contraband, and Addiction

Repeatedly, parole officials pressed Erik on his contraband cell phone use. He admitted paying up to $1,000 for phones and allowing other inmates to use them.

He described the phones as an escape, a way to connect with his wife and the outside world. "I really became addicted to the phones," Erik said. He acknowledged watching YouTube videos, calling loved ones, and even viewing pornography.

Only in 2024, when the possibility of parole became real, did Erik claim to change his behavior. He told the board that a criminal thinking class helped him realize that contraband phones can damage the prison environment as much as drugs do.

Alcohol, Drugs, and Regret

Menendez admitted that at times he drank alcohol in prison and even used heroin briefly. He said the choices stemmed from misery and hopelessness. "If I could numb my sadness with alcohol, I was going to do it," he told commissioners.

By 2023, he said, he decided to quit drugs altogether, marking his mother's birthday that year as a turning point. "From 2013 on I was living for a different purpose. My purpose in life was to be a good person."

Rehabilitation Efforts

Despite his disciplinary record, Erik and his brother Lyle have played visible roles in rehabilitation programs at Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility.

They have launched initiatives in anger management, meditation, and hospice care. Erik himself provided daily assistance to a World War II veteran convicted of sexual violence, saying it was a way to make amends for what his father had done.

Lyle has led a project to beautify the prison grounds, including painting a 1,000-foot mural. Erik contributed artwork to the initiative.

Still, board members remained skeptical, saying the positive letters describing Erik as a "model inmate" minimized the gravity of his misconduct.

The Emotional Weight of the Case

Erik's testimony showed flashes of remorse. He apologized directly to his family, many of whom continue to support both brothers. "I just want my family to understand that I am so unimaginably sorry for what I have put them through," he said. "If I ever get the chance at freedom, I want the healing to be about them."

But his own words undercut him at key moments. His explanation for the murders shifted back and forth. His record of prison infractions contradicted the "model inmate" image. And his past involvement with gangs and contraband raised fresh concerns about whether he could live safely outside prison walls.

Ultimately, the board ruled that Erik Menendez remains a public safety risk. Commissioner Barton cited not only the brutality of the 1989 murders but also Erik's long history of violations behind bars.

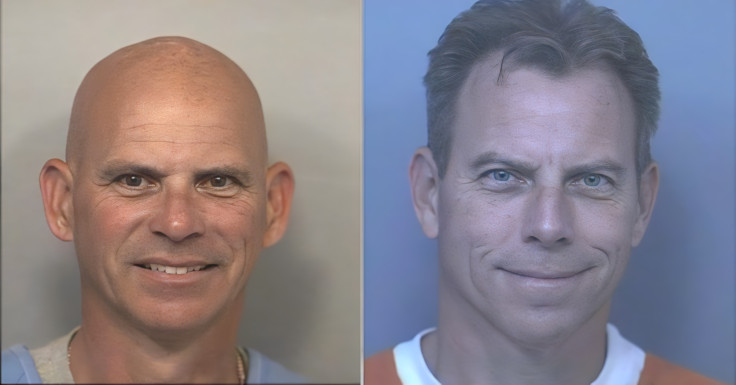

The decision means Erik will remain in prison until at least 2028, when he can request another hearing. By then, he will be 57 years old. His brother Lyle with the parole board is on Friday August 22.

The Menendez brothers' case remains one of the most infamous in American criminal history. Their story continues to spark debates over abuse, justice, and accountability. But for now, Erik Menendez will remain behind bars, his bid for freedom once again denied.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.