Decades after Georgia abolished disenfranchising poll taxes and literacy tests aimed at African American voters, another Latinos in the state’s second largest county are ringing the alarm on voter discrimination. The Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials asked that Spanish-language ballots be prepared for voters in the 2016 election, but the local election board voted down the proposal 4-1 on Tuesday, according to the The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. If Latinos in Gwinnett wanted Spanish-Language ballots, the board said plainly, they would have to sue them or get an order from a higher state authority.

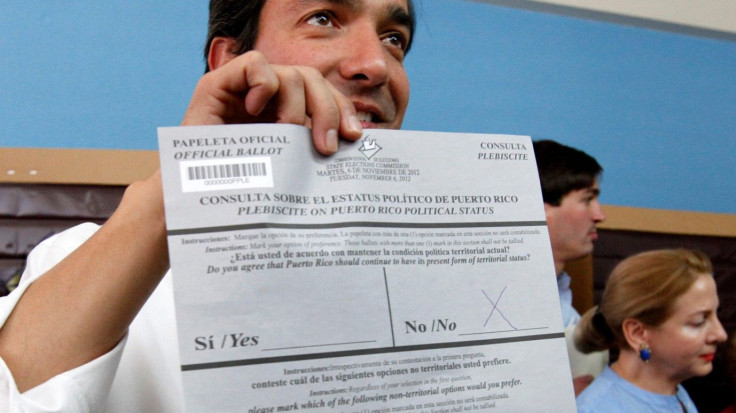

If sued, Gwinnett may have trouble mounting a defense. The U.S. has no official national language and many jurisdictions recognize Spanish as an official or de facto language. That’s not just because of immigrants, but also historical expansions of U.S. territory to places like New Mexico and Puerto Rico where residents were crossed by the border, and not the other way around. Immigrants enjoy legal protections as well, and are guaranteed access to voting materials in their native language under the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Gwinnett’s election board members aren’t the ones uncomfortable with the demands of Latino activists and disinterested in the historical discrimination of Spanish-speaking voters. On Wednesday, state Rep. Doug Collins, a Republican from neighboring Gainesville went on record with the The Atlanta Journal-Constitution rejecting the “proposals” without acknowledging that the laws are already on the books.

“There is no reason to create a new burden on counties with an initiative that will have little impact for its citizens,” he said. “Unreasonable demands by activist groups do not establish justification to change policies, especially when American citizens already have the right to bring translators with them to polling places.”

The balance between the burden on counties and the impact on citizens appears to be spelled out in the Voting Rights Act itself. Gwinnett’s Puerto Rican population of 13,000 is reason enough to merit ballots under the VRA, not to mention rest of the 170,000 Latinos in the county (some of whom are likely foreign-born U.S. citizens).

Collins is right that anyone can bring a friend or family member (or activist) to the polls to help them vote. Yet anyone who speaks another language understands that a loose translation doesn’t provide a crisp picture of the ballot but more a foggy blur.

A weak, rushed, or informal translation is unlikely to impede a Spanish-speaker from finding a representative to check a box for. But it might make the difference with the legalese of a ballot initiative or constitutional amendment. Not to mention the added burden of getting someone to accompany you to the polls. It might not be a poll tax, but it is certainly taxing.

Gwinnett’s requirement that voters to use an English ballot is closer to Georgia’s now-defunct literacy tests. Except instead of targeting blacks by exempting illiterate whites (through a grandfather clause), the measures target immigrants and residents of acquired territories who don’t meet local expectations on what it means to be an American.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.