For years, Chicago's Latino neighborhoods have been facing an environmental crisis.

Industrial facilities and heavy diesel traffic on the West and South Sides have pumped high levels of particulate matter into predominantly Latino and Black communities, which can have serious effects on people's health.

Particulate matter (PM) is a term used to describe the mixture of solid particles of dust, dirt, soot, or smoke found in the air. PM 2.5 is particularly dangerous for people, as the particles are small enough in diameter to be inhaled. According to the EPA, sources such as smokestacks and construction sites can emit particulate matter.

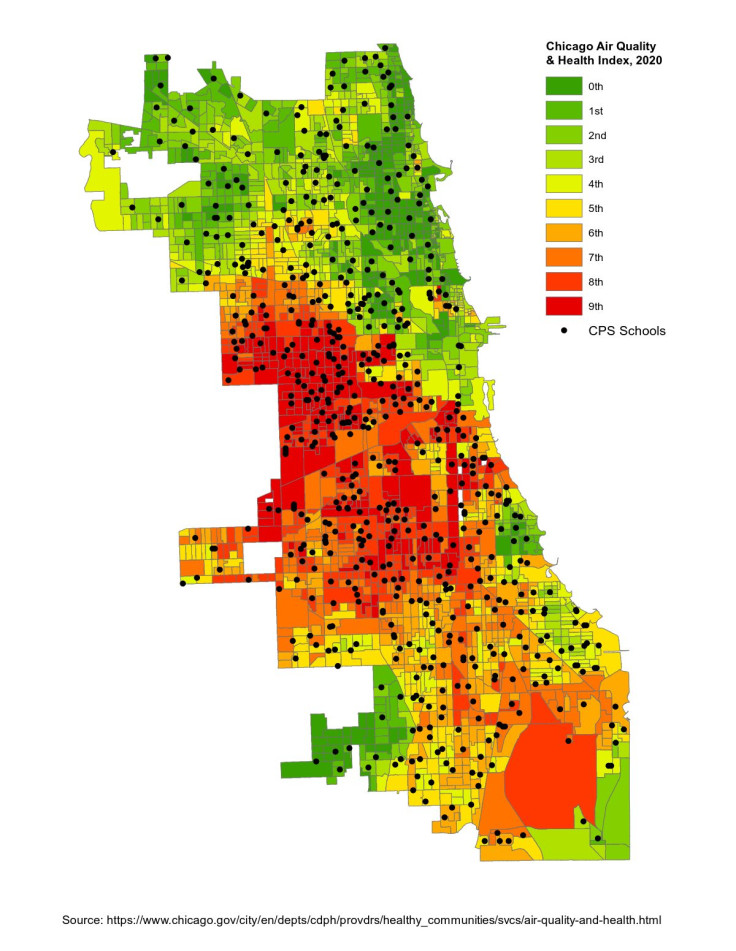

In 2020, Chicago commissioned a study to analyze air quality and health around the city and found that air quality in underserved communities of color was significantly worse than in white, affluent neighborhoods. And as a result, Latino and Black residents have an increased risk of contracting chronic illnesses due to the high levels of PM 2.5 in their communities.

"Communities with low socioeconomic status and high rates of chronic health conditions are especially vulnerable to the impacts of air pollution," reads the report.

Despite the findings, former mayor Lori Lightfoot facilitated the relocation of General Iron, a metal shredding and recycling facility, from the affluent Lincoln Park neighborhood to a majority Latino neighborhood on the South Side. General Iron has a long history of complaints for causing loud explosions and excessive air emissions.

In response to the announcement that the facility would relocate to the South Side, community groups organized and protested the decision. Several community members even staged a month-long hunger strike against the relocation. Eventually, a judge denied the facility's operating permit and prevented the facility from opening.

In the McKinley Park neighborhood, an area with a large number of Hispanic families, residents faced a similar struggle when MAT Asphalt, an asphalt plant that opened in 2018 next to a school, community park and residential area.

The plant remains open despite incurring fines for air pollution and operating without a permit.

These events are fairly standard in Chicago's communities of color and go back several years. One of the most recent examples was the blotched smokestack demolition in the Little Village neighborhood that blanketed the community in a thick fog for several hours.

The most blatant showing of the city's disregard for environmental safety in communities of color came in the 1990s, when the city used North Lawndale, a majority-Black neighborhood, as an illegal dumping group and created a six-story mountain of debris.

Recently, there have been a few wins for the Latino neighborhoods facing environmental challenges. In October, a judge once again blocked General Iron from opening after it argued in circuit court that it should be allowed to open. And residents potentially have an ally in the city's mayor, Brandon Johnson. Johnson, who was elected as a progressive, stated throughout his campaign that environmental justice would be a big part of his agenda. During a budget meeting, he proposed re-establishing the city's Department of Environment, which was removed as a money-saving effort in 2012.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.